Every November, the designer and artist Bernat Klein would plant around 300 bulbs in the garden of his modernist home in the Scottish borders. His daughter Shelley remembers his excitement in spring when the blooms would emerge in a blaze of colour. She tells me his first great love was the Rococo design of the parrot tulip, but he also adored anemones, roses, poppies and irises.

Flowers, for Klein, were happy things: a source of inspiration for both his painting and textile designs. The impact of nature on his imagination was powerful: alongside memories of the parched, yellow-grey tones of the landscape surrounding his childhood town of Senta in former Yugoslavia (now Serbia) and the intense summer blues of the sea in the South of France, where he liked to holiday, his palette is saturated in references to the earth and sky that surrounded his home. Windswept fields of purple heather, dense green forests, an explosion of bluebells or snow drops; icy rivers and vast skies, all are intimated in translucent washes and swathes of sculptural pigment which often took months to dry.

Born in 1922, Klein studied at the Bezalel School of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem from 1940 to ’45. After the war, he emigrated to England, where he continued his studies in Leeds. In 1952, he founded his company in the Scottish Borders, where he created the radical textile designs that were snapped up by the important fashion houses of the day, including Dior, Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent, Hardy Amies and others; he also worked as a consultant and industrial designer for numerous British and Scandinavian firms.

His innovations included a technique called ‘space-dyeing’: a single yarn that contains a multitude of colours.Klein’s earliest paintings were abstract arrangements influenced by colourists such as Joseph Itten, Wassily Kandinsky and Georges Seurat. By the 1970 and ’80s, he was regularly painting flowers from his garden – either wild, or those he had planted – and still lifes of the myriad bottles he liked to collect. He moved fluidly between different approaches: abstraction and figuration commingle in intense rhythms of riotous beauty: they often recall stained glass windows, backlit by a dazzling sun.

The relationship between Klein’s textile designs and artworks was symbiotic – the one would inform the other. At times, he would take a section from a painting, blow it up and then screenprint it or replicate it in a weave. He often stretched one of his fabrics onto a support, and used samples of tweed, wool, mohair or ribbon as collage materials for an artwork. It was a melding that frequently resulted in a near-psychedelic intensity: vivid areas of paint floating above a kaleidoscopic sea.

Although a deeply intellectual man, Klein’s approach to painting was emotional and intuitive; his first and best critic was his beloved wife Margaret, who was also a designer. Shelley believes that her father’s art practice was his way of reclaiming a semblance of joy after the unspeakable horrors of the war: his Orthodox Jewish mother was murdered at Auschwitz, and many other family members died in the Holocaust. At heart, Klein was an optimist who believed in the utopian tenets of modernism: that a new and better world could emerge from the ashes of the 20th century.

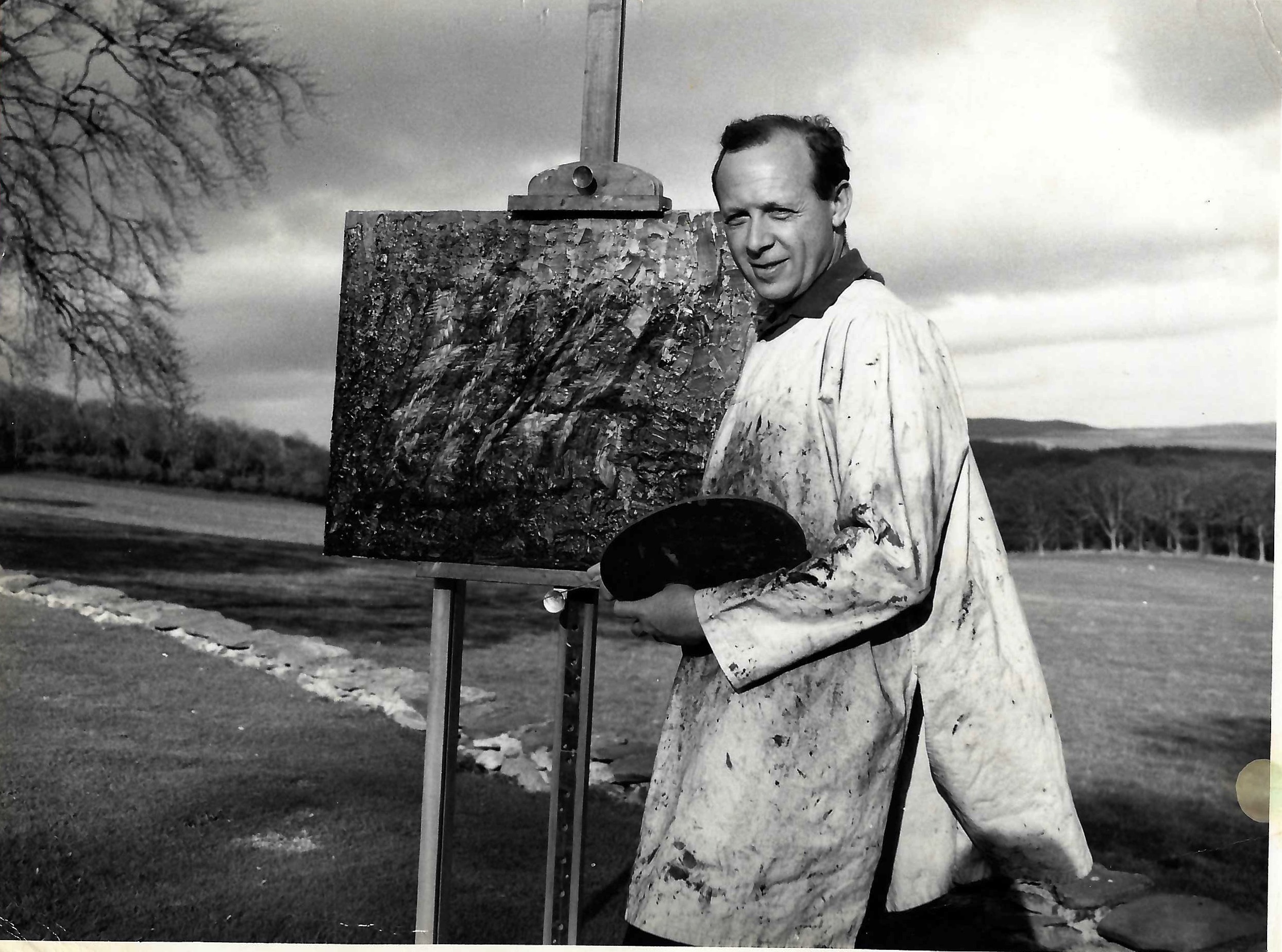

I often visited Shelley and her father at their home in High Sunderland. Klein’s easel was set up by one of the enormous windows overlooking the untrammelled scenery he loved so well, his palette a mess of experimentation, his smock – which he used for more than 50 years – a study in bright splattered paint. He worked with a fervour that never dimmed.

In an interview from 2011, when he was in his late 80s, Klein made clear that painting, for him, was a way of expressing the inexpressible: ‘My passion for colour,’ he said, ‘has grown almost into an obsession. I think colours are as important in our lives as words.’ In his hands, a flower, a landscape or an abstract design are at once entities in themselves and yet – like all great paintings – somehow more than the sum of their parts: symbols of hope, of resurrection, of possibility.